Section 3: Functions

Python provides several built-in functions like print(), input() and len(), but you can also write your own functions.

A function is like a mini-program within a program.

➊ def hello():

➋ print('Howdy!')

print('Howdy!!!')

print('Hello there.')

➌ hello()

hello()

hello()The first line is a def statement ➊, which defines a function named hello(). The code in the block that follows the def statement ➋ is the body of the function. This code is executed when the function is called, not when the function is first defined.

The hello() lines after the function ➌ are function calls. In code, a function call is just the function’s name followed by parentheses, possibly with some number of arguments in between the parentheses.

A major purpose of functions is to group code that gets executed multiple times. Without a function defined, you would have to copy and paste this code each time, and the program would look like this:

print('Howdy!')

print('Howdy!!!')

print('Hello there.')

print('Howdy!')

print('Howdy!!!')

print('Hello there.')

print('Howdy!')

print('Howdy!!!')

print('Hello there.')- Always avoid duplicating the code, as updating would be a hassle.

- With programming experience, you will find yourself deduplicating code, which means getting rid of duplicated or copy-and-pasted code.

- Deduplication makes your programs shorter, easier to read, and easier to update.

def Statements with parameters

- Values passed to

print()orlen()function, are called arguments. They are typed between parentheses.

➊ def hello(name):

➋ print('Hello, ' + name)

➌ hello('Alice')

hello('Bob')The definition of the hello() function in this program has a parameter called name ➊. Parameters are variables that contain arguments. When a function is called with arguments, the arguments are stored in the parameters. The first time the hello() function is called, it is passed the argument 'Alice' ➌. The program execution enters the function, and the parameter name is automatically set to 'Alice', which is what gets printed by the print() statement ➋.

- The value stored in a parameter is forgotten when the function returns. For example, if you added

print(name)afterhello('Bob')in the previous program, the program would give aNameErrorbecause there is no variable namedname.

Define, Call, Pass, Argument, Parameter

The terms define, call, pass, argument, and parameter can be confusing. Let’s look at a code example to review these terms:

➊ def sayHello(name):

print('Hello, ' + name)

➋ sayHello('Al')To define a function is to create it, just like an assignment statement like spam = 42 creates the spam variable. The def statement defines the sayHello() function ➊.

The sayHello('Al') line ➋ calls the now-created function, sending the execution to the top of the function’s code. This function call is also known as passing the string value 'Al' to the function.

A value being passed to a function in a function call is an argument. The argument 'Al' is assigned to a local variable named name. Variables that have arguments assigned to them are parameters.

It’s easy to mix up these terms, but keeping them straight will ensure that you know precisely what the text in this chapter means.

Return Values and return Statements

Calling a len() function with an argument such as 'hello, will evaluate to the integer value 5, which is the length of the string passed.

The value that a function call evaluates to is called return value of the function.

While writing a function, return value should be used with return statement.

A return statement has:

- The

returnkeyword - The value or expression that the function should return.

When an expression is used with a return statement, the return value is what this expression evaluates to.

The None Value

In Python, there is a value called None, which represents the absence of a value(a placeholder). The None value is the only value of the NoneType data type.

- Other programming languages might call this value

null,nil, orundefined. - Just like the Boolean

TrueandFalsevalues,Nonemust be typed with a capital N. - This value-without-a-value can be helpful when you need to store something that won’t be confused for a real value in a variable.

- One place where

Noneis used is as the return value ofprint().

The print() function displays text on the screen, but it doesn’t need to return anything in the same way len() or input() does. But since all function calls need to evaluate to a return value, print() returns None. To see this in action, enter the following into the interactive shell:

>>> spam = print('Hello!')

Hello!

>>> None == spam

TrueBehind the scenes, Python adds return None to the end of any function definition with no return statement. This is similar to how a while or for loop implicitly ends with a continue statement. Also, if you use a return statement without a value (that is, just the return keyword by itself), then None is returned.

Keyword Arguments and the print() Function

Keyword arguments are often used for optional parameters. For example, the print() function has the optional parameters end and sep to specify what should be printed at the end of its arguments and between its arguments (separating them), respectively.

By default, two successive print statements would print their arguments on a separate line, but we can change this behavior with keyword arguments:

print('Hello', end=' ')

print('World')When different strings are concatenated, we can use:

print('Hello!' + 'World', sep=':')The Call Stack

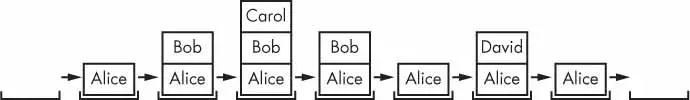

Imagine that you have a meandering conversation with someone. You talk about your friend Alice, which then reminds you of a story about your coworker Bob, but first you have to explain something about your cousin Carol. You finish you story about Carol and go back to talking about Bob, and when you finish your story about Bob, you go back to talking about Alice. But then you are reminded about your brother David, so you tell a story about him, and then get back to finishing your original story about Alice. Your conversation followed a stack-like structure, like in Figure 3-1. The conversation is stack-like because the current topic is always at the top of the stack.

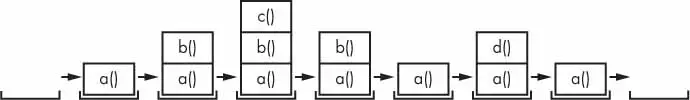

Similar to our meandering conversation, calling a function doesn’t send the execution on a one-way trip to the top of a function. Python will remember which line of code called the function so that the execution can return there when it encounters a return statement. If that original function called other functions, the execution would return to those function calls first, before returning from the original function call.

def a():

print('a() starts')

b()

d()

print('a() returns')

def b():

print('b() starts')

c()

print('b() returns')

def c():

print('c() starts')

print('c() returns')

def d():

print('d() starts')

print('d() returns')

a()Output of this program looks like this:

a() starts

b() starts

c() starts

c() returns

b() returns

d() starts

d() returns

a() returnsThe call stack is how Python remembers where to return the execution after each function call.

The call stack isn’t stored in a variable in your program; rather, Python handles it behind the scenes.

When your program calls a function, Python creates a frame object on the top of the call stack. Frame objects store the line number of the original function call so that Python can remember where to return. If another function call is made, Python puts another frame object on the call stack above the other one.

When a function call returns, Python removes a frame object from the top of the stack and moves the execution to the line number stored in it. Note that frame objects are always added and removed from the top of the stack and not from any other place.

The top of the call stack is which function the execution is currently in. When the call stack is empty, the execution is on a line outside of all functions.

Local and Global Scope

Parameters and variables that are assigned in a called function are said to exit in that function’s local scope.

Variables that are assigned outside all functions are said to exist in the global scope.

- A variable must be one or the other; it cannot be both local and global.

- Think of a scope as a container for variables. When scope is destroyed, all variables stored inside it are forgotten.

- There is only one global scope, and it is created when your program begins. When your program terminates, the global scope is destroyed, and all its variables are forgotten.

- A local scope is created whenever a function is called. Any variables assigned in the function exist within the function’s local scope. When the function returns, the local scope is destroyed, and these variables are forgotten.

Scope matter because:

- Code in the global scope, outside all functions, cannot use any local variables.

- However, code in a local scope can access global variables.

def spam():

print(eggs)

eggs = 42

spam()

print(eggs)- Code in a function’s local scope cannot use variables in any other local scope.

- We can use the same name for different variables, if they are in different scopes.

- It’s easy to track down a bug caused by a local variable. When there are thousands of lines of code, global variables are hard to work with.

Using global variables in small programs is fine, it’s a bad habit to rely on global variables as your programs get larger and larger.

The Global Statement

To modify a global variable from within a function, we can use a global statement.

If you have a line such as global eggs at the top of a function, it tells Python, “In this function, eggs refers to the global variable, so don’t create a local variable with this name.”

def spam():

➊ global eggs

➋ eggs = 'spam'

eggs = 'global'

spam()

print(eggs)Above code evaluates to:

spamBecause eggs is declared global at the top of spam() ➊, when eggs is set to 'spam' ➋, this assignment is done to the globally scoped eggs. No local eggs variable is created.

There are four rules to tell whether a variable is in a local scope or global scope:

- If a variable is being used in the global scope (that is, outside all functions), then it is always a global variable.

- If there is a

globalstatement for that variable in a function, it is a global variable. - Otherwise, if the variable is used in an assignment statement in the function, it is a local variable.

- But if the variable is not used in an assignment statement, it is a global variable.