Asymptotic Notation

So far, we analyzed linear search and binary search by counting the max number of guesses we need to make. But what we really want to know is how long these algorithms take. We are interested in time not just guesses. The running time of both include the time needed to make and check guesses.

The running time an algorithm depends on:

- The time it takes to run the lines of code by the computer

- Speed of computer

- programming language

- The compiler that translates program into machine code

Let’s think more carefully about the running time. We can use a combination of two ideas.

- First, we need to determine how long the algorithm takes, in terms of the size of its input. This idea makes intuitive sense, doesn’t it? We’ve already seen that the maximum number of guesses in linear search and binary search increases as the length of the array increases. Or think about a GPS. If it knew about only the interstate highway system, and not about every little road, it should be able to find routes more quickly, right? So we think about the running time of the algorithm as a function of the size of its input.

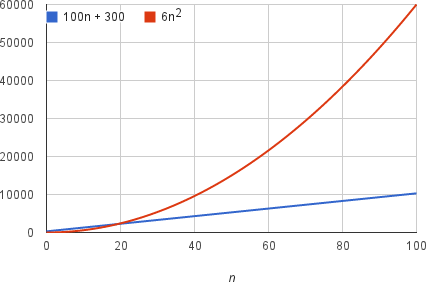

- Second, we must focus on how fast a function grows with the input size. We call this the rate of growth of the running time. To keep things simple, we need to distill the most important part and cast aside the less important parts. For example, suppose that an algorithm, running on an input of size $n$, takes $6n^2+100n+300$ machine instructions. The $6n^2$ term becomes larger than the remaining terms, $100n+300$, once $n$ becomes large enough, $20$ in this case. Here’s a chart showing values of $6n^2$ and $100n+300$ for values of $n$ from $0$ to $100$:

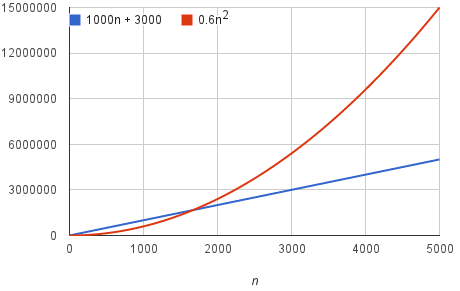

We should say that running time of this algorithm grows as $n^2$, dropping the coefficient 6 and the remaining terms $100n+300$. It doesn’t really matter what coefficients we use; as long as the running time is $an^2+bn+c$, for some numbers a > 0, b, and c, there will always be a value of $n$ for which $an^2$ is greater than $bn+c$, and this difference increases as $n$ increases. For example, here’s a chart showing values of $0.6n^2$ and $1000n+3000$ so that we’ve reduced the coefficient of $n^2$ by a factor of 10 and increased the other two constants by a factor of 10:

The value of $n$ at which $0.6n^2$ becomes greater than $1000n+3000$ has increased, but there will always be such a crossover point, no matter what the constants.

By dropping the less significant terms and the constant coefficients, we can focus on the important part of an algorithm’s running time—its rate of growth—without getting mired in details that complicate our understanding. When we drop the constant coefficients and the less significant terms, we use asymptotic notation. We’ll see three forms of it: big-$\Theta$ (theta) notation, big-O notation, and big-$\Omega$ (omega) notation.